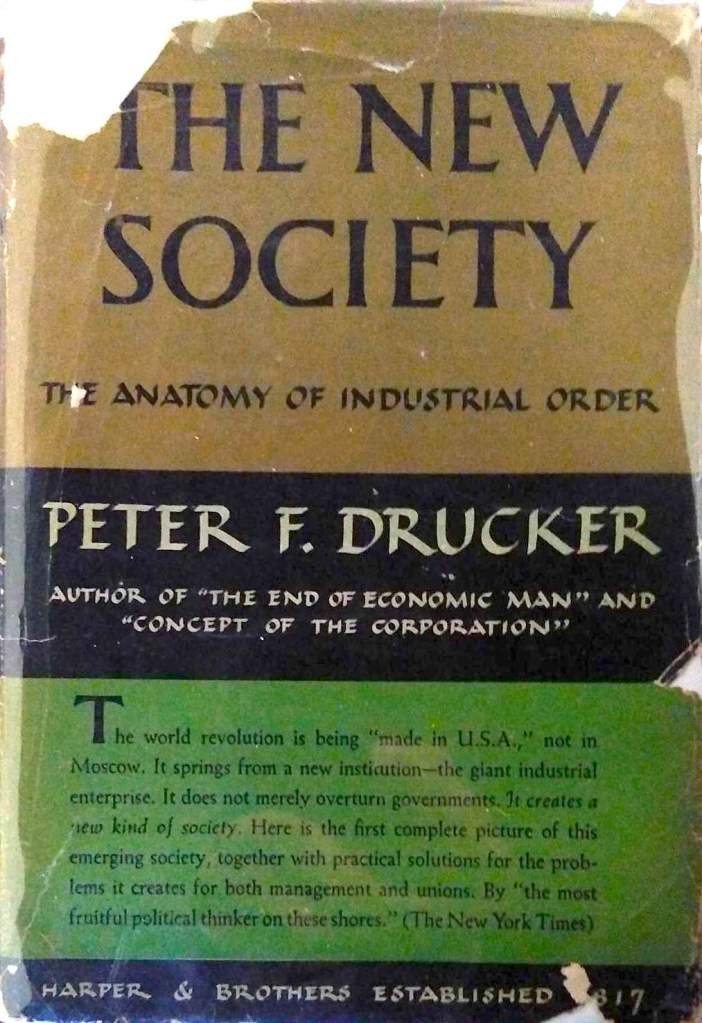

I forget what exactly prompted my interest in Peter Drucker lately. His name came up in connection to some progressive traits regarding business management. With that in mind, an AI search revealed that one of his contributions to business management is “the need for organizations to focus on their social responsibilities”. This seemed compelling enough for me to check out his book The New Society. Looking for some exciting reading? This 1947 book might not be it. But there are some solutions worth considering for the problems Drucker finds with worker-ownership in the new industrial society described by this icon of business management.

Pertinent to this blog is chapter ten, “Can Management Be a Legitimate Government” where he doesn’t use the term governance, but he describes large work places as having a kind of “government.” Spoiler alert: he is unimpressed with worker ownership. He describes any kind of worker-owned business or ‘socialist’ management as a failure. Businesses can’t possibly manage the business, he claims, and manage the well-being of labor. Managers manage, and investors inevitability own the business legally, making no room for workers who must except that there cannot be a “government for the people” in a business.

But in a separate chapter he also describes a problem still present today in such business structures: absurdly high CEO compensation. It is due to “…the hierarchical structure of the big enterprise operating, as it does, in a society in which authority and responsibility are primarily expressed by money income.” He’s not a fan: “executives in a large company will break their necks to get a little more money.” He doesn’t see a solution: “Actually, the problem of the big executive incomes – despite its seeming pettiness – is one of the very hardest to crack.”

Work-ownership intentionally reduces the lowest to highest pay ratios of 1 to 5 on average, even including large international cooperatives. Therefore, maybe we have a solution, while producing “more and cheaper goods for the consumer, that is, for the entire society.” Worker-ownership doesn’t have to be equated with utopia for workers, but as a practical solution.

Drucker accuses workers of resenting enterprise profit because it is surplus that doesn’t go to the worker. What if it did? Drucker sees the very dignity of the workers affected by their aversion to business profit. Sharing profit can maybe provide the dignity, or at least enough dignity to provide rewarding livelihoods to workers. Writers and thinkers emphasize that workers want dignity; from Victor Hugo to Jane McAlevey (see the previous CoopMatters blog post). But wouldn’t it also solve the CEO compensation problem? Further, could it also solve Drucker’s “divorce of ownership and control” where outside investors maintain detached ownership.

Drucker addresses large industrial American businesses. Large co-ops can be a challenge to manage. But as a previous CoopMatters blog post shows, there are many large cooperatives today that use different approaches to governance. But specifically, a case study in worker-ownership could drawn from a business Drucker mentions that still exists today. It is the American Cast Iron and Pipe Company (ACIPCO), an industrial business so quintessentially American that the name of the company is “American” for short.

Drucker describes the company as a worker-owner failure. So, I used a resource that Peter Drucker didn’t have, AI, to look up the company. Started in 1905, it became worker-owned in 1924. Drucker quotes a worker-owner there who was part of a movement to unionize the business “against their own company and against their own management,” as Drucker put it. I would reframe such unionization as for their own company and for their own management. There is nothing wrong with a unionized worker-owned cooperative business. Also, the worker was quoted after more than twenty years of worker-ownership at ACIPCO. So something must have worked. In 1979 ACIPCO implemented an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP). An ESOP does not necessarily mean that workers govern the business, but profits are shared. So Mr. Drucker and I both have to concede something about the management of ACIPCO. Complete control of this extremely successful business appears to be largely out of the hands of workers, which suits his argument, but that profits are shared, and workers have board positions, which suits my argument.